By Dana S Bourgerie, Project Director –

As I have read recently posted interviews, I have been in awe of the resilience demonstrated in the stories. The narratives are often painful and harrowing but also inspiring. Many are epic stories of survival and of unimaginable heartbreak.

Samath An’s path spans from his birth in the remote Oddar Meanchey Province (adjacent to Thailand in Northern Cambodia) to his retirement as a skilled machinist in the Seattle-Tacoma’s aerospace industry. Along the way, he studied in a Cambodia college, married four times, served in Lon Nol’s military, fought the Khmer Rouge, escaped genocide, and found faith in God.

Growing up simply but almost idyllically on his village farm, he describes it thus:

I have many memories, especially in the countryside—the forests and mountains, in the farms, finding food to eat from nature. That time was very happy, and there were plenty of animals and fruits—everything was plentiful. Even though we had no machines, we had enough; it was never a problem. It was easy living. And memories of my parents—they worked as farmers, and us kids—we had many memories with them. As I’ve grown up, I’ve always remembered those memories, and they have taught me well. They’ve taught me to be a man of kindness like they were.

But as with millions of Cambodians of his generation, peace was shattered by war, by the horrors of the mass starvation, and by the atrocities wrought by Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge. He fled his village, narrowly escaping death as Khmer Rouge soldiers executed most of the residents. He chillingly recounts:

The entire village was taken and murdered—the entire village. They separated the children, the men, and the women, and killed them all. All the people in Kampong Tuk.

Samath An required all his wits in a day-to-day struggle to survive. Feigning ignorance, he buried deep his education while using his military expertise to outmaneuver his Khmer Rouge tormentors:

During that time, they would ask me, “Do you know how to read?” And I would answer that I didn’t. “Do you know how to write?” And I again told them, “No, I don’t.” … I ripped my shirt and pants and then sewed them back together, so I looked uneducated. I pretended like I didn’t know anything—to read, to write, anything. But while I did that… I watched them. Figuring out what they liked to do, studying what their weak points were, so that when they were going to take me to be killed I knew what to do to escape from them. I studied all of them, learning.

In a harrowing week-long foot journey to Thailand, he subsisted on leaves of the trees in which he slept, as he strapped himself to the branches by vines. He sometimes walked backwards over freshly swept dirt roads to confound his soldier-pursuers along the way.

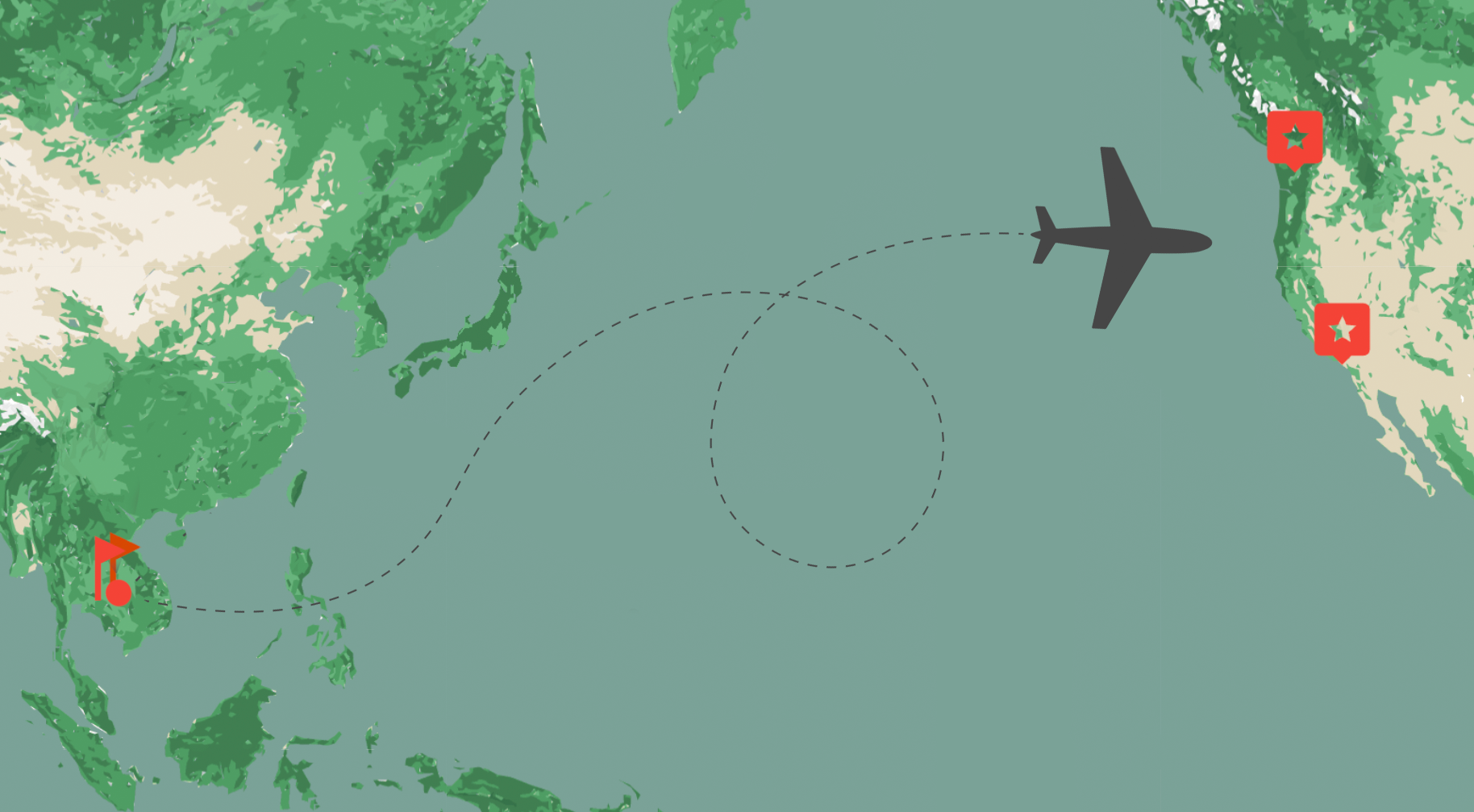

Finally making it across the border––near starvation––he gorged on watermelon and was taken at gunpoint by a farmer whose field he had invaded. He was turned over to local authorities and detained as a suspected Khmer Rouge spy. As a result he was held in a dark detention cell for three months before being released to a refugee camp at the intervention of the American embassy, which had record of previous work with the U.S. military. After a stay in the Philippines, he found his way to rural Iowa to join the construction team of his sponsor, and finally landed in Tacoma, Washington. Samath An’s journey is as unlikely as it is remarkable.

But the project has documented other of these epic life journeys––each, it seems, would make compelling cinema. “Nike” Chheang Chab’s starving father sold him into servitude to a Thai merchant for a bag of rice. He escaped to a refugee camp, and was later sponsored by an American family in Long Beach, California. Rising from poverty and attaining some education, he found work in the county sheriff’s office, established a family, and became a church leader. Still, he was not bitter, but wondered why he had found stability and happiness––unlike the family who had sold him.

Nike’s quest to understand his fate set in motion a miraculous series of events that led to a reunion on a rainy night at the Cambodia-Thai border with the father who gave him up to servitude. Not only does he hold no malice toward his family but has returned––like Joseph of Israel––to help them as a result of his relative prosperity.

These are stories of survivors who, beyond odds, endured their journeys––step-by-step––with heartbreak and suffering. They faced painful choices and bear scars from their ordeals.

As a young girl early in the Pol Pot era, Sok Hen survived by crawling from village to village, hiding in holes to avoid gunfire and falling bombs. Faced with an awful choice of fleeing separately or risking life in her village, her father chose to stay together, which cost him his life. The family faced unthinkable choices daily. She recalls:

An old relative came running to my home and told my father “You need to run! They are already coming to take you away!” My father replied, “I’m not running because my mother is old and in this house. I’m not running anywhere. If they kill all of us together, then so be it.

These heroic stories inspire partly because they are about ordinary people doing extraordinary things in unimaginable circumstances. Often they were confronted with terrible moral quandaries and did not escape unscathed or unscarred—the pain endures. Many whom we interview only now are ready to share the stories of their remarkable journeys.